Opinion: Intel is on the path to chip manufacturing exit

That is unless the US government chooses to ramp subsidies for R&D and capital expenditure to see Intel through what are set to be a difficult few years.

Intel has confessed its 7nm manufacturing yield is a year behind its internal roadmap (see Intel goes foundry for 7nm due to yield issues) and said the solution to this problem is the use of foundry manufacturing services. The stock market reacted badly to the revelation and marked Intel down from about $60 to about $50 per share.

Such major manufacturing transitions have happened many times before and can take many years, but Intel is identifiably on the slope to fab-lite or specialized fab status. The more it uses foundries, the more it supports their case and diminishes its own reason to stay in leading-edge manufacturing. The list of companies that have undergone the journey is long including: AMD, Globalfoundries, IBM Microelectonics, STMicroelectronics, Infineon, NXP Semiconductors and Texas Instruments, to name but a few.

Intel – despite being the largest semiconductor company by revenue – is not immune. But if Intel is no longer a leading-edge chip manufacturer it is not clear that there are any More-than-Moore strings to its bow. If Intel goes fab-lite it would also come under technical and economic pressure to go fabless.

In a conference call with financial analysts to discuss 2Q20 financial results CEO Bob Swan said Intel would continue to invest in its manufacturing process technology roadmap but that the company would be pragmatic about using the best process available – internally or externally. Given that Intel is no longer best-in-class in semiconductor manufacturing, and is unlikely to get there any time in the next five years, it would appear that Intel will be investing large sums of money to little purpose. Something that investors are unlikely to tolerate for long.

Next: Delays at 10nm, 7nm

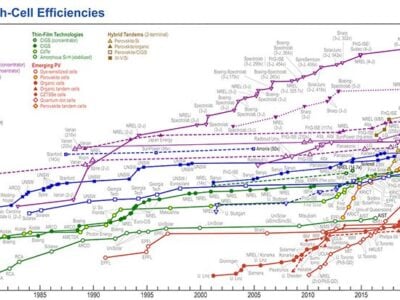

Over the last few years Intel has had numerous delays of its 10nm manufacturing process and now the same problem is effecting the bringing up of its 7nm process. A year’s delay can often be reason enough to drop a node altogether but the leading-edge is now so expensive that it is almost impossible to recover from a dropped node. It effectively spells the end of participation at the leading-edge. The most obvious reference here is Globalfoundries (see GloFo rethinks its future, drops 7nm FinFET).

While Intel’s revenues and profits right now are being boosted by the Covid-19 pandemic, the recessionary ‘morning-after’ is yet to come and Intel’s problems with manufacturing will at some point start to hit its bottom line.

Intel has partly adopted the fab-lite business model by default as it acquired fabless chip companies that were working with TSMC. But CEO Bob Swan is drawing on that playbook more and more heavily. And that can quickly become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

This is because margins are reduced on foundry-produced chips giving the fabless or fab-lite chip vendor less funds to spend on R&D and capex. If Intel starts to lean heavily on foundries for 7nm manufacturing so that it can get competitive products out the door in a timely manner, it will be even less likely to be able to afford to develop the technology for future nodes. In addition, it will have less experience of manufacturing at 7nm putting it at a disadvantage against the competition at a future node. That is unless it can leap on a discontinuity in the miniaturization roadmap and suddenly show an advantage over TSMC.

But CEO Bob Swan said Intel is “pragmatic” about manufacturing: “We will continue to invest in our future process technology roadmap, but we will be pragmatic and objective in deploying the process technology that delivers the most predictability and performance for our customers, whether that be in our process, external foundry process or a combination of both,” he said in the 2Q20 financial conference call.

Next: Going lighter

Not surprisingly the analysts focused on the manufacturing issue in questions. In their answers Swan and CFO George Davis re-iterated the fab-lite gospel many times. “We are also focused on maintaining an annual cadence of significant product improvements independent of our process roadmap,” said Swan.

Swan asserted that the manufacturing policy is not a change but a continuation of the past, saying: “We’ve been designing our products and advancing our packaging technologies, so that we have much more flexibility to decide if and when we will use our fabs or somebody else’s.”

One analyst specifically went to the implications for capex. Swan answered: “In the event we decide that we’re going to leverage third-party foundries more effectively, we would add a little more 10 [nanometer capex] and a lot less 7 [nanometer capex].”

And that cutting back on capex at the leading-edge can get addictive.

One analyst characterized Intel’s fab-lite status as 20:80 with 20 percent of its manufacturing being external and 80 percent internal. Swan did not object to the characterization and indicated that over time Intel will likely be using more foundry services. “So, in general, I would say for planning purposes, we’ve been engaging with the ecosystem much more. And all else equal, I would expect that roughly 20 to 80 percent to be a little bit higher as we focus on growing the business,” Swan said.

Next: What’s lacking

In a free and open market I would predict a fairly rapid transition for Intel from fab-heavy to fab-lite and on to fabless. One thing that acts as a boat anchor on that process is what to do about the wafer fabs and thousands of people employed in them, In Intel’s case those plants are all around the world. Such considerations can turn a fairly obvious direction of travel into death by a thousand cuts over the course of a decade or more.

Look to the example of IBM, which remained a manufacturer of silicon and owned wafer fabs for far longer than made commercial sense for a big iron company that had turned into a consultancy and services company.

In the case of AMD it may be remembered that the company found a fast solution to its manufacturing “problem” in the form of the sovereign wealth fund of Abu Dhabi that wanted to get the Gulf state into semiconductors and bought out AMD’s manufacturing interests to form Globalfoundries.

The other obvious inhibition on Intel abandoning chip manufacturing is US government policy (see US talks to Intel, TSMC about building local foundry fabs). It is notable that China’s leading foundry – Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp. (SMIC) – is not at the leading-edge in manufacturing but Chinese government support and a strong ecosystem of has helped that company draw closer to it.

Intel may yet take the US government’s dollar to continue to dabble in chip manufacturing for the sake of US government policy on strategic necessities. Swan portraying an Intel that is becoming ambivalent about ownership of leading-edge semiconductor manufacturing may have the side-effect of helping him to negotiate with a US government that will be required to pay substantially for R&D and capex.

But R&D and capex alone does not secure leadership at the leading-edge edge of semiconductor manufacturing. It also takes the vision and a desire to lead, sustained over many years. Right now, Intel seems to be lacking both.

Related links and articles:

News articles:

Intel goes foundry for 7nm due to yield issues

GloFo rethinks its future, drops 7nm FinFET

US talks to Intel, TSMC about building local foundry fabs

Intel announces ‘Ponte Vecchio’ discrete GPU

Intel apologies for another supply shortfall

Graphcore launches 7nm AI processor

AMD launches x86 processor in 7nm

TSMC becomes world’s biggest chip company

Chiplet manufacturing gains interface bus upgrade, PHY generator

More details emerge of Apple’s eviction of Intel processors from PCs

If you enjoyed this article, you will like the following ones: don't miss them by subscribing to :

eeNews on Google News

If you enjoyed this article, you will like the following ones: don't miss them by subscribing to :

eeNews on Google News